A 16th-century murder-mystery which is essentially an interactive book, with soap opera elements, tough choices and a glorious final twist – Pentiment is most definitely not your average run-of-the-mill game.

Recently, gamers of a more intellectual bent have quietly despaired at the modern trend towards games-as-a-service, in which any hints of meaning or attempts to be thought-provoking have been sacrificed on the altar of landfill “content” usually involving your character’s virtual outfit. But sections of the games industry have been fighting back against that TikTokification of games. Including Obsidian, Pentiment’s developer, noted for the likes of The Outer Worlds, Grounded, Neverwinter Nights 2 and Fallout: New Vegas.

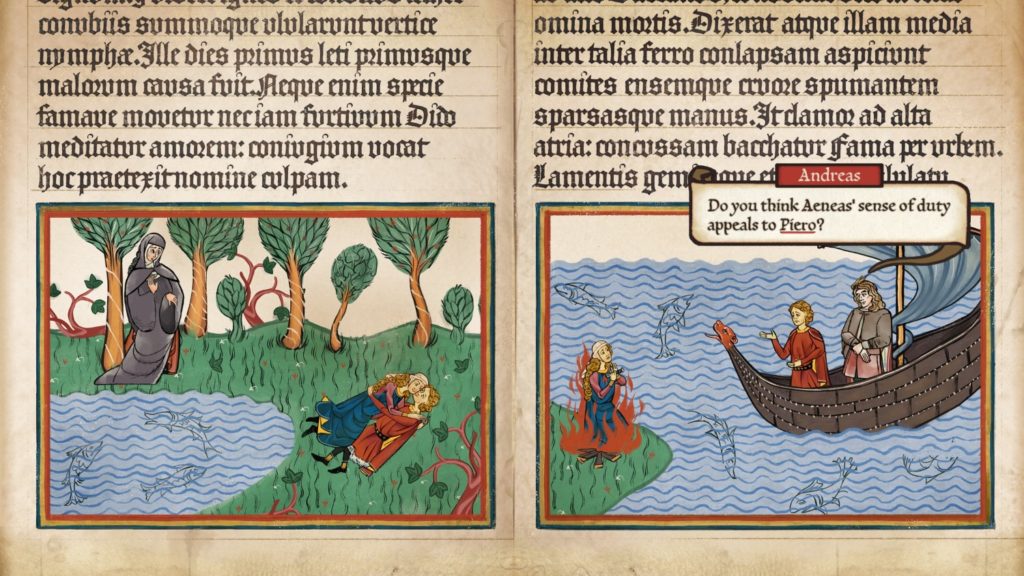

Pentiment is the absolute polar opposite of any game-as-a-service. For starters, it is a game obsessed with books, and not just any books: the books created by hand in monasteries, with extravagant penmanship and exquisite illustrations, before printing presses became prevalent. Gameplay-wise, you would describe Pentiment as a point-and-click adventure. But we reckon it would be more accurately characterised as an interactive book.

Pentiment focuses on a specific place and time: the peasant village of Tassing, in the Bavarian Alps, in the early to mid-16th century. A period in which – a pedant might point out – printing presses were starting to come to the fore, and indeed Tassing has a printer among its ranks. But it is also dominated by its Catholic Abbey, with an accompanying nunnery, whose book-creating scriptorium, despite in danger of becoming an anachronism, is a major source of income.

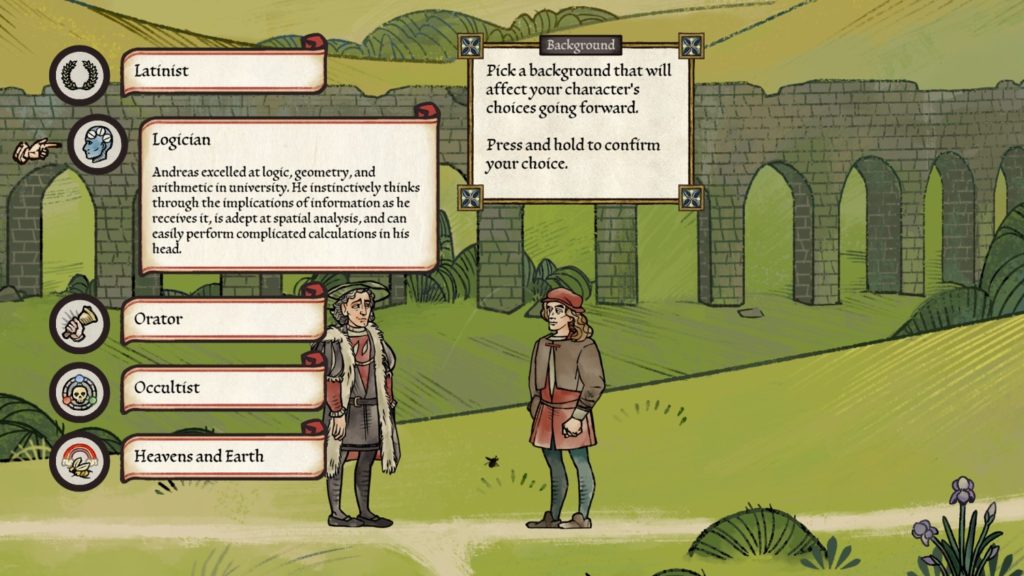

And that’s where the character you play (at least initially), Andreas Maler, works. Maler is an outsider among the abbey’s monks: having dropped out of university, he is working as an illustrator in the scriptorium as the first step on the road to becoming a master artist.

Andreas is also an outsider among the village-folk, since he’s middle-class and moderately privileged, and Tassing’s inhabitants very much live a peasant lifestyle, paying taxes to the abbey and somewhat at the mercy of the mill-owner. Lodging with a family in the village is something of an eye-opener for him, and while working in the scriptorium, he is also trying to complete a masterwork which will set him on the path to becoming a renowned painter.

Initially, Pentiment is all about getting to know Tassing’s geography and conversing with its inhabitants. Life at the abbey is very regimented, with set meal-times and the like, and Pentiment reflects that – cutely, whenever a meal-time arises, he can find a local family to eat with, and thereby get to know them better.

Heading up to the abbey to work, Andreas encounters Baron Rothvogel – a somewhat racy character, but the pair bond on an intellectual level, partly helped by the back-story that you’ve been invited to choose for Andreas. Before long, the baron has been murdered and Andreas’s friend and scriptorium colleague Piero – so old that his work is hopelessly slow – finds himself accused of the murder, by dint of being first on the scene. It’s up to Andreas to find out who really dunit.

Which proves much more of a responsibility than it sounds, due to the harshness of life in the 16th century – any murderer will be punished by death, and because the baron was a friend of the Prince-bishop, the church is sending an Archdeacon to adjudicate on the murder. So you only have a few days, and must embark on an exhaustive path of questioning subjects, tracking down clues and making sense of them.

As that process unfolds, you unwittingly learn a vast amount: Pentiment is a gloriously educational game, without feeling in the least bit didactic. For example, you receive a crash-course in the nascent rise of Martin Luther and the challenge that Protestantism is about to pose to the Holy Roman Empire, as well as the extent to which the church fulfilled the role of government in the middle ages.

As you explore Tassing’s more off-the-beaten-track environs and talk to its inhabitants, you start to piece together a sense of the village’s history – it has been settled since Roman times, and Roman ruins still abound. Perhaps most importantly, you get to know each of the village’s families, and even while you work on solving your murder-mystery, you can do things for them which could have consequences later.

Thus Pentiment generates the feeling of a book, with a village-sized cast of characters; an impression which is reinforced by the fact that it covers a span of 25 years; in its latter stages, you take control of a character who wasn’t even born when the game started. And – as you may have noticed from the accompanying screenshots – it looks like a 16th-century book, too, with a naïve but endearing inked art-style and a sense of perspective which, deliberately, is slightly flattened and dodgy.

As its labyrinthine plot unfolds – Baron Rothvogel’s murder isn’t the only one to be solved, and events, allied to greater awareness of the teachings of Martin Luther, erode the church’s authority – you get to witness social change as it sweeps through vast areas of Europe which were previously more or less feudal. And your – to an extent reluctant — position at the centre of events makes it an even more engrossing experience.

Those seeking fast-twitch gameplay won’t find that in Pentiment – it does have a number of mini-games, but the vast bulk of its gameplay lies in conversing with characters and getting them to reveal things they would rather keep secret. At times, the game lets you know that you have a chance to extract such a nugget of information, and your frequent failure to do so leaves you yearning to embark on another play-through.

That’s despite the fact that Pentiment is vastly longer and more ambitious than other point-and-click adventures – a play-through will take the best part of 20 hours. Thanks to its sheer depth and intricacy, it feels more like an RPG, regardless of gameplay – it’s always a good sign when a game proves tricky to classify. And thanks to the fact that you can pick the back-stories of the characters you play, it ends up being vastly replayable. You also have to bear in mind Andreas’s state of mind – he has a dream-place that he often visits, and the choices you make for him take a toll on his mental health, and are reflected – and reflected upon – in that place.

If the idea of living a vicarious life in a peasant village in the 16th century, and witnessing the first stirrings of a lifestyle that we would recognise as modern, sounds like a brilliant conception, you’ll love Pentiment. It’s a game designed to broaden the mind, educate via stealth and leave you reflecting on how so many of the life elements we take for granted nowadays were absent for centuries – if you think inequality is bad now, it’s a good job you weren’t around in 1518, when Pentiment starts.

Pentiment is the perfect antidote to the dispiriting array of mindless shooters in which you do the same thing over and over again in search of a better set of virtual clothes, and as such, it exposes the increasing banality and superficiality of the 2020s in a brutal yet hugely welcome manner.